At Slate’s History Vault, Rebecca Onion introduces a letter from Rose Wilder Lane to Laura Ingalls Wilder, her mother and the author of the Little House series of books.

At Slate’s History Vault, Rebecca Onion introduces a letter from Rose Wilder Lane to Laura Ingalls Wilder, her mother and the author of the Little House series of books.

A lot of good books have addressed the question of authorship and co-authorship in the Little House books; see John Miller, Ann Romines, Anita Clair Fellman, and William Holtz’s biography of Lane, The Ghost in the Little House, for just a few of them.

Reading Wilder’s “Pioneer Girl” manuscript, the letters between the two women, and the books of both (including Wilder’s essays for farm publications) gives an entirely different perspective than simply reading the Little House series.

The letter at Slate does sound a little peremptory and irritable, but if you read Wilder’s letters in return or those excerpted in Holtz’s biography, you’ll see that in occasional impatience and irritability, Lane didn’t fall far from the maternal tree. In the letter, Lane scolds Wilder for writing that Laura threatened Cousin Charley (remember Charley? The boy who cried wolf, or rather bees?) with a knife when he tried to kiss her at age twelve: “Maybe you did it, but you can not do it in fiction.” Maybe you couldn’t put it in fiction, but that Laura, like the one who cut school to go roller-skating when she was in high school, would make an interesting and lively character in the real story of her life.

Lane was a major figure in her own right. An award-winning short story writer, a traveler, a working journalist, a novelist: she was the famous writer long before the Little House books put her forever in the shadows as Baby Rose of The First Four Years.

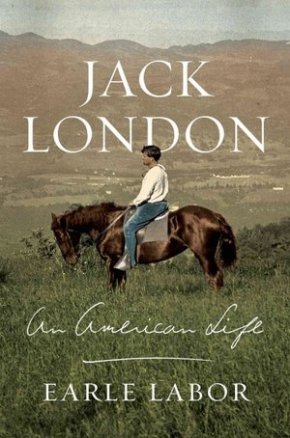

I’ve written about Wilder‘s Little House books, about Lane’s pioneer fiction, and about her biography of Jack London, but she’s a fascinating figure who deserves more attention.