The current Stephen Crane bibliography and the new Call for Papers for Stephen Crane panels at ALA are now up at the Crane Society site: http://www.wsu.edu/~campbelld/crane/index.html.

Identity of Hannah Crafts (The Bondswoman’s Narrative) Revealed

From this morning’s New York Times :

In 2002, a novel thought to be the first written by an African-American woman became a best seller, praised for its dramatic depiction of Southern life in the mid-1850s through the observant eyes of a refined and literate house servant.

Gregg Hecimovich and Reverend Joseph Cooper

John Wheeler lived on the plantation where Hannah Bond escaped slavery.

But one part of the story remained a tantalizing secret: the author’s identity.

That literary mystery may have been solved by a professor of English in South Carolina, who said this week that after years of research, he has discovered the novelist’s name: Hannah Bond, a slave on a North Carolina plantation owned by John Hill Wheeler, is the actual writer of “The Bondwoman’s Narrative,” the book signed by Hannah Crafts.

Beyond simply identifying the author, the professor’s research offers insight into one of the central mysteries of the novel, believed to be semi-autobiographical: how a house slave with limited access to education and books was heavily influenced by the great literature of her time, like “Bleak House” and “Jane Eyre,” and how she managed to pull off a daring escape from servitude, disguised as a man.

The professor, Gregg Hecimovich, the chairman of the English department at Winthrop University in Rock Hill, S.C., has uncovered previously unknown details about Bond’s life that have shed light on how the novel was possibly written. The heavy influences of Dickens, for instance, particularly from “Bleak House,” can be explained by Bond’s onetime servitude on a plantation that routinely kept boarders from a nearby girls’ school; the curriculum there required the girls to recite passages of “Bleak House” from memory. Bond, secretly forming her own novel, could have listened while they studied, or spirited away a copy to read.

Edith Wharton’s Berkshires Home, The Mount

Cross-posted from the new Edith Wharton Society (http://www.edithwhartonsociety.org) site except for this photo of The Mount, which I took a year ago:

Cross-posted from the new Edith Wharton Society (http://www.edithwhartonsociety.org) site except for this photo of The Mount, which I took a year ago:

From NPR:

Gilding the Ages: Edith Wharton’s Berkshire Sanctuary

JARED BOWEN: Even today, Edith Wharton occupies a place as one of America’s leading literary ladies. She was born into the upper crust of old New York in the mid-1800s—a member of high society who also exposed it through the prism of her pen. Wharton wrote more than 40 books in 40 years including “Ethan Frome” and “The Age of Innocence” for which she became the first woman awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. Today she is also remembered for her home, The Mount. And if ever a house could serve as an autobiography, The Mount is it. Situated on a hill overlooking a lake in Lenox, Massachusetts, it was conceived by Wharton from the ground up. She dreamed its location, guided its aesthetic principles and designed her elaborate gardens. It was in a sense, her own “House of Mirth”—which she wrote while living here.

Continue reading: Video and transcript at http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/entertainment/july-dec13/wharton_09-14.html

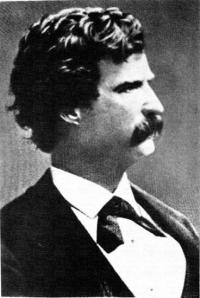

Mark Twain Gives Advice on Conference Presentations

These excerpts from the new Autobiography of Mark Twain address “a new and devilish invention–the thing called an Authors’ Reading” rather than a conference presentation, but Twain has some great advice about what not to do. These are from pages 383-384 in the print version, but you can read it online as well.

Twain had been asked to speak and foresaw disaster: “The introducer would be ignorant, windy, eloquent, and willing to hear himself talk. With nine introductions to make, added to his own opening speech–well, I could not go on with these harrowing calculations.”

1. It takes a long time to create a readable short paper.

“My reading was ten minutes long. When I had selected it originally, it was twelve minutes long, and it had taken me a good hour to find ways of reducing it by two minutes without damaging it.”

2. Time your presentation. Even Howells didn’t know this.

“Howells was always a member of these traveling afflictions, and I was never able to teach him to rehearse his proposed reading by the help of a watch and cut it down to a proper length. He [page 384] couldn’t seem to learn it. He was a bright man in all other ways, but whenever he came to select a reading for one of these carousals his intellect decayed and fell to ruin. I arrived at his house in Cambridge the night before the Longfellow Memorial occasion, and I probably asked [him] to show me his selection. At any rate, he showed it to me—and I wish I may never attempt the truth again if it wasn’t seven thousand words. I made him set his eye on his watch and keep game while I should read a paragraph of it. This experiment proved that it would take me an hour and ten minutes to read the whole of it, and I said ‘And mind you, this is not allowing anything for such[interruptions] as applause—for the reason that after the first twelve minutes there wouldn’t be any.’”

3. Keep it short.

“He [Howells] had a time of it to find something short enough, and he kept saying that he never would find a short enough selection that would be good enough—that is to say, he never would be able to find one that would stand exposure before an audience.

I said ‘It’s no matter. Better that than a long one—because the audience could stand a bad short one, but couldn’t stand a good long one.'”

4. Conference rooms can be stuffy.

“It was in the afternoon, in the Globe Theatre and the place was packed, and the air would have been very bad only there wasn’t any. I can see that mass of people yet, opening and closing their mouths like fishes gasping for breath. It was intolerable.”

5. Don’t belabor the obvious.

“That graceful and competent speaker, Professor Norton, opened the game with a very handsome speech, but it was a good twenty minutes long. And a good ten minutes of it, I think, were devoted to the introduction of Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes, who hadn’t any more need of an introduction than the Milky Way.”

Amlit Updates: Hamlin Garland Bibliography

Updated Hamlin Garland bibliography at http://www.wsu.edu/~campbelld/amlit/garlandbib.htm.

Seamus Heaney (1939-2013)

The great poet Seamus Heaney died recently, sparking an outpouring of well-deserved tributes.

The New York Times: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/31/arts/seamus-heaney-acclaimed-irish-poet-dies-at-74.html?smid=tw-share&_r=0

The Guardian: http://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/sep/01/seamus-heaney-roy-foster-appreciation and http://www.theguardian.com/books/seamusheaney

The Paris Review: http://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/1217/the-art-of-poetry-no-75-seamus-heaney

I had the great privilege of interviewing Mr. Heaney many years ago after writing about his work. Hearing him read in that beautifully sonorous voice and hearing him discuss other poets, especially his contemporaries, was unforgettable, as was his gracious manner.

His last words were “Noli timere”–“Do not be afraid”–and they were texted to his wife.

Pre-Raphaelite Mural Discovered in William Morris’s Red House

From The Guardian:

The near-lifesize figures on the wall at the Red House, now buried in south-east London suburbia at Bexleyheath, are now believed to represent the joint work of Edward Burne-Jones, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, his wife Elizabeth Siddal, Ford Madox Brown and Morris.

“In the morning we had one and a half murky figures, in the evening we had an entire wall covered in a pre-Raphaelite painting of international importance,” James Breslin, property manager at the Red House, said.

“We had no idea what the figures, or the newly revealed inscriptions, represented, but at the Red House it pretty much has to be Chaucer, Arthurian myth or the Bible – all fairly daunting works to start reading line by line.”

The property managers decided to tweet an appeal for people to help identify the text, and Breslin said that within an hour a tweet came back saying “Try Genesis 30:6”, which reads: “And Rachel said, God hath judged me, and hath also heard my voice, and hath given me a son.”

The figures are from the Bible, including Rachel, Noah holding a model ark, Adam and Eve, and Jacob with his ladder – the latter possibly by Morris himself – painted as if on a tapestry furled across the wall.

However the imagery is more complex, because scholars believe it also relates to another cherished pre-Raphaelite Arthurian legend, Sir Degrevaunt who married his mortal enemy’s daughter. But then neither family thought much of Morris’s choice of Janey Burden, the beautiful daughter of an Oxford stable man.

Side note: This was originally tweeted by @HistoryLondon and retweeted by @PaulFyfe, so in addition to helping The Red House to identify the source, Twitter helped to spread the word of the discovery. We’ll be talking about the Pre-Raphaelites in English 372 in a month or two.

Mark Twain: A new discovery about his pen name

Martin Zehr’s “A New Theory Could Solve the Mystery of Mark Twain” in the Kansas City Star profiles a discovery by Twain scholar Kevin Mac Donnell, who presented it at the recent Conference on Mark Twain Studies (the Elmira conference).

Martin Zehr’s “A New Theory Could Solve the Mystery of Mark Twain” in the Kansas City Star profiles a discovery by Twain scholar Kevin Mac Donnell, who presented it at the recent Conference on Mark Twain Studies (the Elmira conference).

From the article:

Mac Donnell made use of the Google Print Library Project, a search tool not available to earlier scholars. He was searching through 19th-century humor magazines when he came across a character in a burlesque sketch by the name of Mark Twain. It was in the Jan. 26, 1861 issue of Vanity Fair, a short-lived but widely read humor magazine of the era Twain is known to have read.

The anonymously published sketch in which the character appears, titled “The North Star,” is a send-up of Southerners at a nautical convention attempting to address the nagging problem of compasses always pointing north.

Successive speakers in the sketch, including Mr. Pine Knott, Mr. Lee Scupper, Mr. Mark Twain, Mr. Robert Stay and Mr. Rattlin, whose names are derivatives of sailing terms, gripe about the problem. The Civil War is about to erupt and will close the Mississippi River, ending Sam Clemens’ piloting career. As used in the sketch, the name Mark Twain is an indication of shallow water for an ocean-going ship, and, by inference, a person lacking depth.

Mac Donnell’s exposition, which appears in a detailed version in the current edition of the Mark Twain Journal, includes the observation that Charles Farrar Browne, aka Artemus Ward, a print and standup humorist Twain admired, was then a staff writer for Vanity Fair.

Mac Donnell’s research fills an important gap in the story by suggesting Clemens’ likely familiarity with the piece two years following its publication.

Media History Digital Library

The Media History Digital Library (http://mediahistoryproject.org/) has expanded its holdings in film magazines to include Variety from 1905-1926 and a host of others from all parts of the moviemaking industry, from technology to fan magazines. Here’s a partial list just from of the early cinema journals:

Exhibitors’ Times (1913)

Film Fun (1916-1926)

The Film Index (1910)

The Great Selection: First National First Season (1922-1923)

The Implet (1912)

Motion Picture Story Magazine (1913)

Motion Picture Studio Directory and Trade Annual (1916-1918)

Moving Picture Weekly (1916-1918)

Moving Picture World (1907-1919) – NOW COMPLETE FROM 1907 TO JUNE 1919!

National Board of Review Magazine (1926-1928)

The Nickelodeon (1909-1911)

The Photoplay Author (1914-1915)

The Photo-Play Journal (1916-1921)

The Photo Playwright (1912)

U.S. vs. Motion Picture Patents Company (1912-1913)

Variety (1905-1926)

The Writer’s Monthly (1916)

Some of these are at archive.org, but the organization at the Media History Digital Library makes them far easier to find. If you write about early film and don’t know about this resource already, it’s well worth a visit.

Biography Corner: John Hay’s Literary Network

I’m only up to the year 1895 in listening to John Taliaferro’s All the Great Prizes: The Life of John Hay, but it’s clear that what others are seeing as a bug in the biography is something I’d call a feature: its focus on the literary rather than the political side of Hay’s life. Historians like Louis L. Gould in the Wall Street Journal and Heather Cox Richardson in the Washington Post have faulted Taliaferro’s lack of emphasis on politics, but for the literary historian, it offers a passing parade of nineteenth-century characters:

I’m only up to the year 1895 in listening to John Taliaferro’s All the Great Prizes: The Life of John Hay, but it’s clear that what others are seeing as a bug in the biography is something I’d call a feature: its focus on the literary rather than the political side of Hay’s life. Historians like Louis L. Gould in the Wall Street Journal and Heather Cox Richardson in the Washington Post have faulted Taliaferro’s lack of emphasis on politics, but for the literary historian, it offers a passing parade of nineteenth-century characters:

- The Five of Hearts, including Henry Adams, the tragic Clover Adams, subject of a fine recent biography by Natalie Dykstra; and the mercurial Clarence King, whose amazing double life is told in Martha Sandweiss’s fascinating social history and biography of King, Passing Strange.

- The usual suspects: Lincoln, for whom (as anyone knows after seeing Lincoln), Hay served as a private secretary with John Nicolay; Garfield, Grant, James G. Blaine, McKinley, Mark Hanna.

- Our old friend W. D. Howells, with whom Hay shared a lively correspondence as both men seem to have done with everyone else in the nineteenth century.

- The beautiful and elusive Lizzie Cameron, for whom Hay, Adams, and a good portion of nineteenth-century masculine Washington seem to have carried a considerable torch (was she the “It Girl” of the Gilded Age?). She deserves a biography of her own.

- Directly or indirectly: Mark Twain, Henry James, and Bret Harte. The latter’s success inspired Hay to write two popular dialect poems, “Little Breeches” and “Jim Bludso of the Prairie Belle.”

- And Constance Fenimore Woolson, the subject of Anne Boyd Rioux’s new biography project. Hay was related to Woolson through Samuel Mather, and it was Hay who helped arrange and pay for her burial in Rome’s Protestant Cemetery. To Henry Adams, he wrote (I’m paraphrasing): “We buried poor Constance Woolson today. She did much good in her life, and no harm, and she had no more happiness than a convict.”

Hay’s The Breadwinners, which I read many years ago, is discussed at some length, as is the LIncoln biography and Hay’s poetry.